Scientific History

Approaching A New Genre of History

Without History one remains always a child. -Lorenzo Valla”

This chapter begins to explain history’s transformation from an art to a science during the Renaissance. Many new concepts were introduced to history during this time period, dividing it into genres. History becoming a science was not a unanimous decision. There were, and are to this day, many different perspectives and opinions about where history belongs (the arts or the sciences). Although this transformation of history can be summarized in a chapter, books could be named after it, and is a very large, diverse, and complex topic.

Introduction

The period of history’s transformation began with a single word, humanism. Humanism is defined by historians Judith Bennett and Charles Warren Hollister as

“an intellectual movement whose earliest beginnings are associated with Francesco Petrarch (1304-1374), that Stressed: (a) admiration for classical antiquity, (b) the educational importance of literature, art, and history; and (c) an optimistic assessment of the potential of human beings.”

Donald R. Kelley also identifies humanism by its relationship with medieval humanities, especially grammar and rhetoric. Throughout this chapter, humanism will be related to scientific history through Bennett and Hollister’s definition; admiration of antiquity, educational importance, and optimistic expectation of human beings.

Renaissance humanism had an interest in, and almost a devotion to, classical culture. Humanists during the Renaissance admired the Greeks and Romans above all classic cultures, replicating their morals, social customs, politics, and literary terms. Poetry was valued during the height of classical culture, so it was only natural for Renaissance humanists to draw a parallel between history and poetry. Dionysius of Halicarnassus, a Greek historian from c. 20 BCE, famously agreed that history was philosophy teaching by example and that history is a moral philosophy, related to poetry. Unlike poetry, history is dedicated to providing a literal (most obvious and no exaggeration) and particular (existing only in the context of the time, and not broad) truths.

History was valued as an art. What made history unique was its ties to classical grammar and historical sense. Historical sense is a term used to put the past in the context of the time, T.S. Eliot wrote “The historical sense involves a perception, not only of the pastness of the past, but of its presence”. Optimistic assessment of the potential of human beings.

History as an Art

Renaissance humanism created a genre of writing called the “arts of history.” This type of writing studied the methods of famous authors; Aristotle, Cicero, Quintilian, and more. Much of the writings imitated ancient texts. In addition to imitating these texts, humanist tended to elaborate on them as well.

Leonardo Bruni (1370-1444) was an Italian humanist who is famous for his History of the Florentine People; which was considered one of the greatest works during the Renaissance. Bruni created a new style of writing during his time by trying to give readings more overall meaning, not just a word-for-word translation. Bruni used Livy (59-17), a Roman hsitorian, as a model for his format, style, and language instead of the old medieval style of formatting. Bruni paved the way for modern historiography, acknowledging the importance of history by saying

“knowledge of the past gives guidance to our counsels and our practical judgment, and the consequences of similar undertakings [in the past] will encourage or deter us according to our circumstances in the present.”

For humanists, history was a way to add structure to the world and to understand it better. While truth was enhanced during the Renaissance, there were still doubts about how honest history was. Herodotus (484-425) has been referred to as the father of history, but also the father of lies. Scholars once looked up to Herodotus as one of the creators of history, but as time went on they questioned his approach. This is one example of negative criticism towards the art of history. Kelly expresses his concern with history, by saying it can, unfortunately, lead to the “admiration” of wrongdoers; like Caesar,Hercules, and Cyrus who acquired fame through unjust and often violent actions.

The Method of History

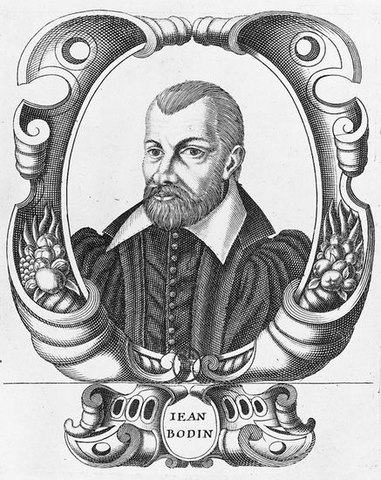

The beginning of historiography was not original to Renaissance humanists. Historiography began as early as Antiquity, from authors like Herodotus and Thucydides. Some sixteenth-century scholars were not satisfied with history being defined as an art; they wanted to apply methodical concepts to make history more of a science. One way to achieve this method was to translate ancient philosophical texts into the context of the modern era. An example of this is seen in Jean Bodin’s Republique.

The love of knowledge, says Aristotle, is natural to all men. It is passion to which the wise men of antiquity were slaves, and which still inflames the learned in our own day. It is the source of all science and of all philosophy. From an etymological point of view, what is the philosophy? It is the love of knowledge (41).

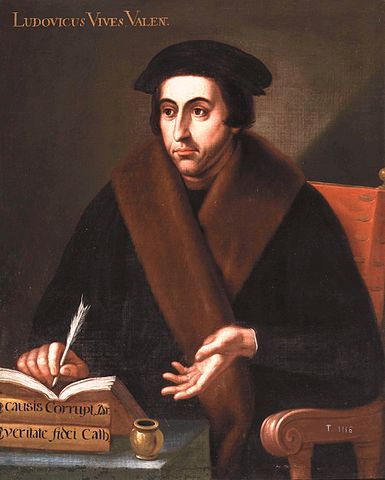

Bodin was a historian, lawyer, economist, and natural philosopher in the sixteenth century. He tried to use history for legal and political purposes, and implied the type of government he wanted was a republic. Renaissance humanists translated literary texts from antiquity with the intention of dictating human decisions; like the way Bodin tries to make Tacitus (56-120) or the Roman Rebublic relevant to his time. The idea that hindsight is 20/20 was appealing and applied to every person. The key for history to become a science was organization. Organization gave structure to knowledge; like a skeleton to an animal. Organization put an emphasis on genealogy (line of decent) which was important to the Ciceronian Laws. The Ciceronian Laws refer to the use of both truth and impartiality to achieve perfection under the influence of rhetoric. Organization also helped the status of a particular topic. For example, the Spanish philosopher Juan Luis Vives was upset that pagan history was better recorded than Christian history.

The difficult part about history is the impossibility of proving dishonesty. There are often times when there are many variations of the same event, “making history filled with impurities” (Kelley). A counter argument to that statement would be history is what it is because of impurities. History brings a singular wisdom, but it isn’t without flaws. History has been negatively influence by political gains, lust, greed, military glory, and/or religious ambition; “Sixteenth-century historians loved the idea of disposition of narrative, the requirements of cause, analysis and critical judgment, the need for impartiality, and the priority (neglected by the ancients) of truth over beauty.”(Kelley). Bartholomaeus Keckerman said history was a mode of arrangement, rather than subject matter. He criticized disorganization, claiming history was only truthful when it was combined with other fields (economics and politics primarily). This process was what began history’s metamorphosis from an art to a science. Common previous sixteenth-century views only addressed particular facts, “lacking the status of particular truth”(Kelley).

History alone was not a science; it had to be applied to reason first and had no further meaning than what it described. Only through reason could sixteenth-century humanists use history as a science; there had to be a reason why the Trojans opened the doors to let the wooden horse into their city, otherwise it is just a list of events. According to Jean Bodin, history was divided into three laws; human, nature, and divine.

The Art of Criticism

In the Renaissance, criticism was finding forgeries in the writing, while making sure all the information given was true. History that had been written long ago was seen with more skepticism than in previous generations. Writings from antiquity were more closely analyzed, and suspected to be untrustworthy. Bude more info/context on who he is wanted a “restitution” of antiquity as a whole. The Renaissance contributed greatly to the transformation of history. A completely new way of writing and reading history developed from this time period,

“The conjunction of these impulses with archaeology and anthropology in a modern sense marked the beginning of an enlightened and truly (if in some cases excessively speculative) philosophical history.”

Critic, a word which began as a medical term, then turned into a literary one, led to an important part of historical development. Debating the great authors of the past was a new way to find a closer truth.

Universal History

Universal history appealed to many people in the sixteenth-century, both religious and secular. Universal history was being challenged, and considered a product of the succession of master narratives. It had little to do with historical methods or criticisms, and focused on origins, general patterns, and final goals.

Need to expand more on Universal history.

Suggested Readings

Antonio Perez-Ramos, Francis Bacon’s Idea of Science and the Maker’s of Knowledge Tradition

Singleton, Charles S., ed. Art, Science, and History in the Renaissance. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1967.

Greenblatt, Stephen. The Swerve: How the World Became Modern. New York: W.W. Norton, 2012.

Jacob, P. L. Science and Literature in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. With over 400 Wood Engravings. New York: F. Ungar Pub., 1964.

Kaufmann, Thomas DaCosta. The Mastery of Nature: Aspects of Art, Science, and Humanism in the Renaissance. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1993.

Wightman, W. P. D. Science and the Renaissance. Vol. 1. Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd, Published for the University of Aberdeen, 1962.

Sarton, George. Six Wings: Men of Science in the Renaissance. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1957.

Mignolo, Walter. The Darker Side of the Renaissance: Literacy, Territoriality, and Colonization. 2nd ed. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2003.

Suggested Primary Sources

Leonardo Bruni, History of the Florentine People

Henry Cornelius Agrippa, Vanity of the Arts and Sciences

Lucian How to Write History

Dionysius of Helicarnassus critique of Thucydides

Lacroix, Paul. Science and Literature in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance: Illustrated with Upwards of Four Hundred. London: Bickers, 1878.

1684 words.