The Importance of Historiography

The notion of absolute fact is a dangerous concept. On one hand, to believe in the existence of ultimate truth prevents oneself from critical thought and therefore limits the mind. While on the other hand, to be overly skeptical renders oneself incapable of building complex notions of the world, for a lack of foundational reason from which to work. In studying history, doubt is not only healthy, but necessary to the pursuit of ‘truth’. The most dangerous histories are those which are believed wholly and without hesitation. Within the realm of historiography, ‘time’, its conception, and measure are open for debate (Momigliano 1966). That is not to say one should not accept certain narratives as fundamentally true or as reasonable explanations. Rather, one should approach history as inherently political, in existence because an individual or group sought to record an event or events as they perceived it to have happened. “History is not indoctrination. It is a wrestling match” (Conway 2015). Writing history should not be viewed as a mission to find the ‘truth’, but rather as an exercise in analyzing perspectives – available data, narratives, prior works, and contemporary outlooks – and creating plausible interpretation. Historian Beverley Southgate posits there is no authoritative truth (Southgate 2005, 87-91), but that to accept a loss of order does not mean to lose the importance of history. In order to understand where we are going, we must know where we have been, with history as our guide and an library of historiographical narratives as our interpreter.

Before one can dive into a collection of historiographic paradigms and frameworks in history, one must first try and understand ‘what is historiography?’ In layman’s terms, historiography is the ‘history of history’. However, this simple understanding of the field only scrapes the surface of its intricacy and importance. Its study is far more than chronology, it reaches beyond the tabling of dates and events. Historiography dives into the intricacies that make up the historical record. The simple student demands ‘facts’ and ‘truth’ in their history, while the wiser questions the authenticity of facts in and of themselves, while understanding truth to be an elusive concept. In order to write good history, one must research good history. It is the interpretations of dates, statistics, and events that create history and turn a simple historical record into historiography. Historiography is not only the physical writing of history, but also the nuance of stories and conglomeration of perspectives. Such interpretation is created with a narrative in mind, writing a story to convey a message, whether that be an explanation of past events or guidance for future actors. “A history is essentially a collection of memories, analyzed and reduced into meaningful conclusions — but that collection depends on the memories chosen… Just as there is a plurality of memories, so, too, is there a plurality of histories” (Conway 2015). The very essence of history – the narrative – can also work against itself. Without narrative and interpretation, one merely has an accumulation of numbers and names, assembled without purpose or clarity. The insertion of narrative opens the historian to potential methodological traps, including bias, omission, and assumption. Historians must work to understanding all these examples in order to produce the ‘best’ and ‘most-balanced’ history possible; an imperfect task whose results can never satisfy all.

Critical thought exists as the truest and most reliable approach to history. As a policy decision, institutions of education should address the duplicity of historiography, and do so from a young age. Simply advocating for a degree of skepticism will go a long way in prompting new generations of historians to question the narratives which their culture embrace. While accepting historical interpretation may be foundationally truthful, encouraging historical skepticism can do much to check extremism and other ‘isms’, such as nationalism or Marxism. There is much to be said for the benefits of national unity and historical idols from whom followers can gain inspiration. However, there is just as much to be said about blind patriotism and demagoguery. Germany often comes to mind as a example of history manipulated for nationalistic purposes. Whether Otto von Bismarck or Adolph Hitler, Germans are particularly notorious for reframing history in order to marginalize groups (most often the Jews) and create a common enemy in order to unite the nation (Popkin 2016, 82-83). 19th-century French scholar Ernest Renan noted on the role of memory and nationalism, “it is good for everyone to know how to forget’; and ‘forgetting’… is a crucial factor in the creation of a nation’ – even when that implies what might seem to entail ‘historical error” (Southgate 2005, 61). Not unlike the Germans, Renan also promoted virulent anti-Semitic rhetoric and racism in his historical ‘interpretations’ (Renan 1900 126-127). American History in the United States is often flawed from its main counters, due to its mutation of facts; for its ability to ‘forget’. One might point to the persecution of indigenous populations or the downplay of African slavery as examples of American historiographic manipulation through negligence. Sometimes, when presented with such differing perspectives, seemingly equal in their burden of ‘facts’, truth becomes more tangible with the critical study of history. Most important to this is the evaluation of narrative and an understanding of selective memory.

The intent of this collection is modest but relevant to students of history and to the evaluation of historical narrative. Through the dissection of historiography, our team has compiled a series of topics and paradigms in which one should analyze history. These themes are either central to the study of historiography (and would be remiss without them), or cover areas believed to be lacking in the academic field (and are sorely needed for its improvement). While some areas of examination are traditional and expected to be included in a compilation of historiographical insight, other areas are commonly overlooked or neglected by academics. Each writer brings their field of expertise and passion to their section, ensuring thoughtfulness and diligence. By collaborating with more than a dozen students of history, each with their own perspectives and focuses of study, this work acts as a uniquely specialized compilation of historiographical themes that spans the breadth of human civilization.

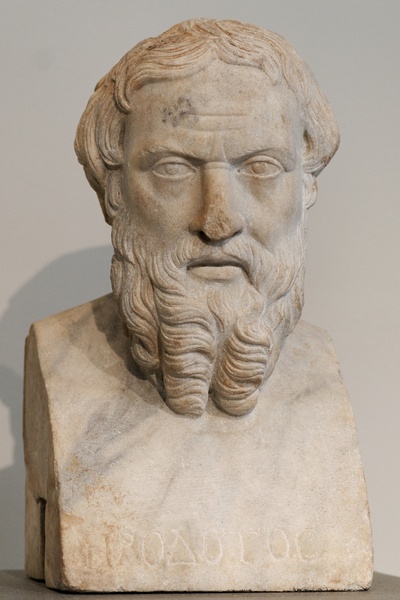

Some certain topics in a text of history’s history are ancient historians and the methodology of some of civilization’s earliest historiography. In a classic sense, our scholars dive into a time before history had any academic inclination; when history truly was limited to myth, and its purpose was to explain the world, sometimes in the most ‘magical’ sense. ‘Fathers of history’, such as Herodotus and Thucydides launched western historiography on a path of progression. In the same vein of ancient western historians, the Romans followed many trends of their Greek predecessors. This relationship between two ancient worlds, and the legacy of their scholarship, set a standard for historical writing that continued long after their empires faded from power. To the detriment of historiography, many texts focus almost exclusively on the centrist – or western – perspective. If one were to rely solely on the average history textbook for one’s knowledge, it would come as no surprise if one had little or no understanding of histories outside of the ‘white’ world. For this reason, corollaries have been featured, exploring the historiographical methods and works of prominent Eastern scholars – from the Near East in the Islamic Kingdoms, to the rich cultural centers of China. While much is to be said of the western world – its contributions and the ways in which it has shaped historiography – the contributions of non-centrist cultures are equally notable and therefore worth space in our collection.

Following the theme of escaping western-centric tunnel vision, our collection dedicates scholarship to the post-colonial movement in historiography. In this analysis, we show how deeply embedded colonial histories are entrenched within those of other nations; how western history permeates and often infiltrates the histories of local hosts in eastern and indigenous cultures. Thinkers like Edward Said – a father of post-colonial history – advocated for ideas of “orientalism”, whereby non-centrist histories took center-stage. Other schools of thought, like subaltern historians led by Dipesh Chakrabarty and his fellow hisotrians at The University of Chicago, developed in response and became seen as more moderate in post-colonial studies. Chakrabarty thought it more prudent to recognize the existence of western bias, but appreciate its contributions for what they are, rather than deny their legacy, as some have accused Said and his followers (Popkin 2016, 146-148). This movement of post-colonialism sparked a broader evolution into post-modern history, whereby intersectionality became more important to the modern scholar.

Marginalized members of society, namely women and minorities, were the focus of post-modern scholarship. Our collection analyzes the controversial philosophies of Michel Foucault and his new perspectives on human sexuality and impossibility of truth; as well as women, gender, and the various waves of feminism. Looking from a 21st century perspective, our scholars look at the progress that has been made in the world of feminist history, even in comparing the post-modern movement from the start of the 1980s to now, a mere thirty years later. Historiography and gender have come a long way since academics first began framing the importance of women in history. In 1986, Joan W. Scott detailed the importance of including gender diversity in the historic record. However, in reading her once-profound perspective, any millennial academic would be remiss not to notice her binary approach to the discussion. In rethinking and rewriting gender history, the modern historian must consider the spectrum of genders and identities in order to be representative and most accurate.

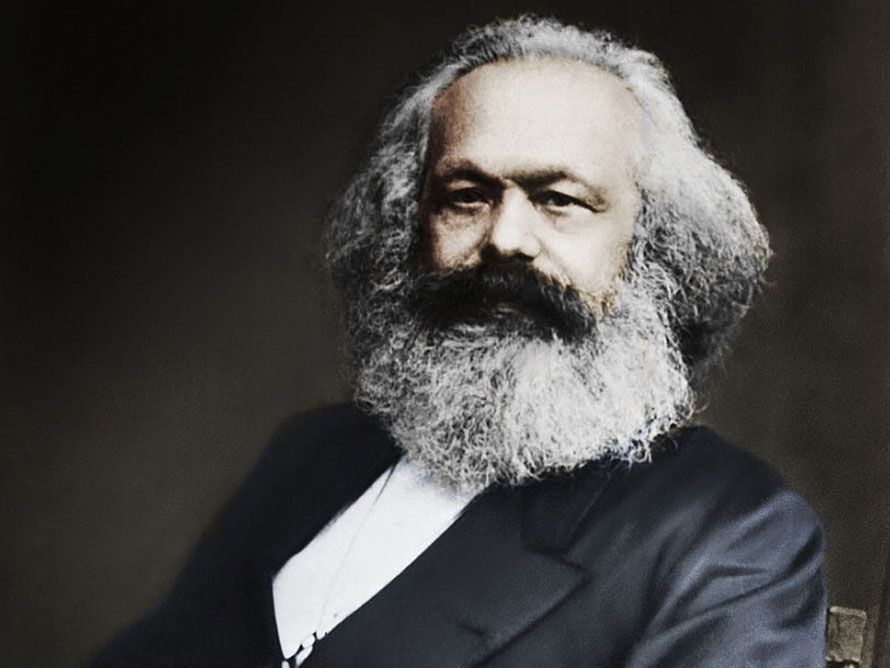

No less important among the social histories, are those pertaining to the common laborer. Much of his work went unanswered when Karl Marx questioned the way in which society viewed its socio-economic structures. Yet, half a century later, his paradigm shift inspired many thinkers and historians – from the Annales School in France, to Chinese Revolutionaries. While historians, up until that point, had focused primarily on the ruling elite, their contributions, and the influence they had on their people, new social historians sought to empower the working class and study their role in the historic record. Such a move gave way to other facets of social history which relied almost entirely on narrative, rather than the ‘professionalized’ history advocated by those like Leopold von Ranke. His ‘scientific’ approach to history was framed entirely around politics. While Ranke did not neglect social or economic aspects, they were positioned within the paradigm of political history (Gil 2009, 385). More than a century later, a quantitative movement of historiography, in many ways, took the field of historiography to a new level of ‘scientific’. Though, this time, as it coincided with birth of many civil rights movements, it became central to new social histories, which often relied on statistics and numbers for analysis (Anderson 2007).

Finally, our collection provides insight into a modern lens on historiography. Contemporary politics have brought reinvigorated arguments of ‘fake news’ into the spotlight. This notion of fact manipulation and truth distortion is inseparable from the study of history and how it is accepted in society. Debates rage on between academics, who champion standards of verification and research, and those who believe history is more subjective than not and, by extension, that facts are malleable. Narrative, perhaps now more than ever, plays a key role in understanding agenda, the inclusion and omission of ‘facts’, and the audience for whom something is intended. Our scholars take on the complexity of ‘History Wars’, as well as the role of film, art, and other media in the telling of history. Film, in particular, popularizes history in a divisive (and often less-than-accurate) way. Historians find themselves asking if it is better the public know history imperfectly, or not at all? Harkening back to the example of American History education, the U.S. is faced often with the dark reality of its idols and role-models in the legacy they wish to project. For better or worse, films like Lincoln and Selma have influenced Americans and altered the perception they have of their leaders.

The country’s founding fathers crafted some of the finest expressions of personal liberty and representative government the world has ever seen; many of them also held fellow humans in bondage. This paradox is only a problem if the goal is to view the founding fathers as faultless, perfect individuals. If multiple histories are embraced, no one needs to fear that one history will be lost (Conway 2015).

Rather than fight for the narrative which best preserves the image of the nation – essentially allowing the narrative to dictate the ‘memory’, the holistic ‘truth’ should be pursued, understanding that multiple perspectives need not compete with one another. In full circle, one must revisit the goals of history and the approach best taken for understanding its purpose. For what do we lose, other than our bias, when learning another’s perspective?

References:

Anderson, Margo. 2007. Quantitative History. The Sage Handbook of Social Science Methodology, ed. William Outwaite and Stephen Turner, London: Sage Publications.

Çaksu, Ali. 2017. “Ibn Khaldun and Philosophy: Causality in History.” Journal of Historical Sociology 30 (1): 27–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/johs.12149.

Carretero, Mario, Mikel Asensio, and María Rodríguez Moneo. 2013. History Education and the Construction of National Identities. IAP.

Chakrabarty, Dipesh. 1992. “Postcoloniality and the Artifice of History: Who Speaks for ‘Indian’ Pasts?” Representations, no. 37: 1–26. https://doi.org/10.2307/2928652.

Conway, Michael. 2015. “The Problem with History Classes.” The Atlantic, March 16, 2015. https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2015/03/the-problem-with-history-classes/387823/.

Gil, Thomas. 2009. “Leopold Ranke.” A Companion to the Philosophy of History and Historiography, 383–92.

Green, Anna, and Kathleen Troup. 1999. The Houses of History : A Critical Reader in Twentieth-Century History and Theory. New York : New York University Press, 1999.

McNeill, William H. 1986. “Mythistory, or Truth, Myth, History, and Historians.” The American Historical Review 91 (1): 1–10. https://doi.org/10.2307/1867232.

Momigliano, Arnaldo. 1966. “Time in Ancient Historiography.” History and Theory 6: 1–23. https://doi.org/10.2307/2504249.

Munslow, Alun. 2007. Narrative and History. Theory and History. Basingstoke : Palgrave Macmillan, 2007.

Popkin, Jeremy D. 2016. From Herodotus to H-Net : The Story of Historiography. New York ; Oxford : Oxford University Press.

Renan, Ernest. 1900. Renan’s Antichrist. London : Walter Scott. http://archive.org/details/renansantichrist00renaiala.

Rockmore, Tom. 2009. “Marx.” A Companion to the Philosophy of History and Historiography, 488–97.

Scott, Joan W. 1986. “Gender: A Useful Category of Historical Analysis.” American Historical Review 91 (5): 1053–75.

Southgate, Beverley C. 2005. What Is History For? Psychology Press.

White, Hayden. 1980. “The Value of Narrativity in the Representation of Reality.” Critical Inquiry 7 (1): 5–27.

Winner, Langdon. 1980. “Do Artifacts Have Politics?” Daedalus, 121–136.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herodotus

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thucydides

2494 words.