In Defense of Madness

Historians themselves (or some of them) have long since been aware of the theortetical complexities inherent in their subject – of the subjectivity involved in assigning causal connections (Southgate, 107)

In a post war world, the late 20th century saw an unprecedented philosophical backlash to the established academic fields that had been hyper focused on objective knowledge. “Postmodernism” arose from the grayish muck of wartime’s hardship and invaded the historical tradition by surprise. Helped along by the revolt against the bastardization of professional history by nationalist wartime powers; postmodernism entered the historical world forever changing the historiographical record. This article aims to describe how the postmodernist models have affected historiography in ways that shook historians code of ethics to their core and why they have created an understandable backlash to their abstract existence.

The Postmodern Experiment of Narrative

“History, meaning, and progress are no longer able to reach their escape velocity. They are no longer able to pull away from the overdense body that slows their trajectory” – Jean Baudrillard The illusions of the end (The Postmodern History Reader,pg.41)

Rarely has one particular school of history caused such controversy within the ranks of historians. Why does such a vehement disdain of this philosophical framework appear when fellow historians fall victim to the postmodernist thought? The simple answer I suggest, is the obstruction of simple obtuse “truth”, a sentiment that implies the loss of greater meaning. History relies the traditional belief on what most believe is a well-structured grand narrative allowing historians to write within a well-defined category building upon past knowledge. The belief in a well-structured narrative fits into an analogy of a house-built brick by brick through the works of countless historians.

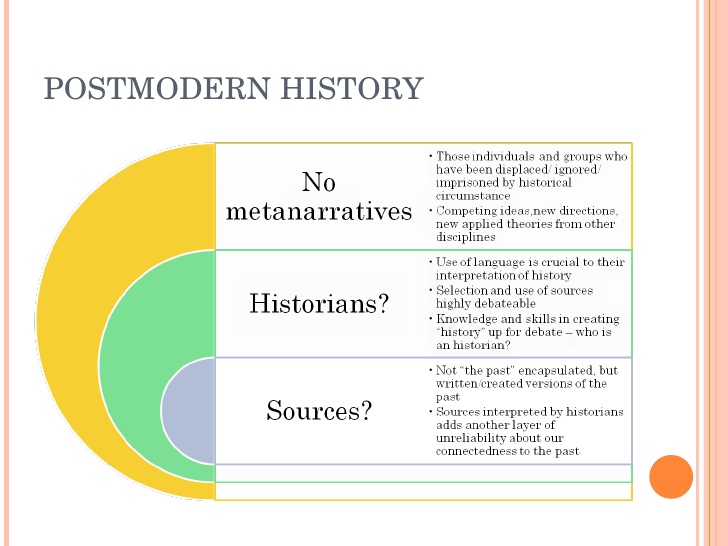

Those who would believe that by the unified methods of various collaborators a collective house will be constructed containing the story of the past. This constructionist categorization of history prescribes an idea that there is an entirely objective element of historical structure that with enough dedication can be completed. The overarching narrative structure of history has three general outlines described by Kathleen Troup and Anna Green in The Houses of History “a master narrative which seeks to explain a broader segment of history; a grand narrative ‘which claims to offer the authoritative account of history generally’; and finally a metanarrative which draws upon some particular cosmology or metaphysical foundation, for example, Christianity.” (Houses, pg. 204) The enticing belief in a total or complete history plays on our basic human desire to find identity in an obscure past but the reality is that history is massively complex and requires an open, abstract view of the past.

Postmodernists reject the total history narrative of older, professional history, and because of this they open themselves up to the divisiveness of their own historical structure.** To those still gripping onto the old Rankean model it seems as if Postmodernists have thrown away a meaningful purpose from professional history, what good is history if it does not present answers for truth? Postmodernists, however, have other, layered, goals in mind for their work. For the postmodernist, history exists within an abstract realm of generalized form. Postmodernists may use history not to define a rigid past but to question the complacency of our own basic understanding of the past.

Michel Foucault

Michel Foucault (1926-1984) believed that the dissecction of meaning in history existed far beyond traditional models of analytical histories. One of many postmodernist historians, Foucault stood out as a particularly divisive figure. His writing is abstract, strange, and challenging; picking apart the intellectual structure of the world around him. To even bring Foucault into a discussion of historiography is challenging because of the chaotic nature of his own intellectualism. Gary Gutting’s Foucault: A Very Short Introduction compiles a short summary of Foucault’s own personal history, Gutting best felt that Foucault operated within nontraditional role of historical writing that was Rebellious in nature, the histories Foucault wrote were reactionary to the internal frustrations and hardships that challenged him in his life. He targeted the accepted social behaviors and developments in the fields of medicine, psychiatry, sex, and crime, “He always had an interest in and sympathy for those excluded by mainstream standards.” (Gutting, pg. 24) Foucault felt strongly that society needed to begin questioning our histories through the conceptual categories we create for our own understanding. What troubled Foucault was blind acceptance of learned conditions and instead challenged readers to begin examining the categorical bias we impose or simply allow in our daily lives. It is his own personal philosophy that he translates into a historical approach that is unique among scholarship because it exists outside of standard meticulous source citation; instead Foucault lives within a conceptual realm of narrative; understanding his own narrative inserts a profound aspiration to celebrate isolated aspects of histories as meaningful lessons from the past.

Foucault’s desire to question the histories we had commonly accepted extended deeper than the subjects addressed in his own historical writing, what emerged was foundational elements to engaging history with a sense of exploration and nostalgia. To this end, Foucault’s histories exploded into abstract nightmares for strict “proper” historians who owed all knowledge to deep archival interaction. Because of Foucault’s fundamental flaw of not rooting his work in the traditional historical method, it’s difficult to utilize Foucault’s literal writing in a serious professional work, however, his message extends past words he’s written because he invokes the need to understand narrative and meaning in all texts.

The Meaning of Nothing

“from one semantic to syntactical change, can one recognize that language has turned into rational discourse.” (Michel Foucault, the Birth of the Clinic, pg.xi)

Meaning in text is at the center of postmodern scholarship. The evaluation of narrative in historical scholarship challenges the pretense of well-defined truth. Naturally, postmodernist’s felt that truth was not easily obtainable through strict research alone. Instead, history, to postmodern thinkers was a truth that existed as a relative ideal found within the context of societies current culture. Truth within history is meant to be expressed for the purpose of narrative storytelling. This is not meant to say that all history is made up, or should be cherry picked by the historian to create destructive narratives, the difference comes from interpretation alone. Allowing group identity to be warped by fictitious beliefs of their past is harmful not only to that group but to the stability of their society. It would be mad to exclude commonly held historical fact in dates from histories and as a general rule Postmodernists will dissect a larger meaning from the archives. This lessons they learn can be individualized for the reader or author and is dependent on the manner in which the historical facts are analyzed.

Postmodernists accept that there is a general, factual basis that history rests upon. Without the historian pulling together these elements of fact into a cohesive meaning then historical fact becomes trivial. The historian must function as a non-fiction storyteller. The crucial element for any story teller is the narrative and purpose of the history they portray. The quality of the historian can help impart meaning where none may have been previously; this elevates the historian, who holds tremendous power over the narrative they illuminate.

When a postmodernist examines the purposes of narrative in history they make a conscious effort to realize the biases they have in the discourse of a topic. The examination of these narrative biases are crucial to the presentation of the past as fact. Postmodernists are hesitant to explicitly state that their explanation of the past is the most accurate depiction. “To Speak about the thoughts of others, to try to say what they have said has, by tradition, been to analyze the signified”(Foucault, Clinic,pg. xvii). The idea of a grand historical narrative is too complex to ever expressly accept the fact of causation within the past. Too many unexplainable and missing variables exist in the past to dictate why one historical actor behaved the way they did. So, we must examine the meaning behind the actions, the reasons why such actions or symbols were important in development, and accept that the answers might always be ambiguous. The most controversial element of postmodernist history will always be the unyielding element of questioning accepted historical “fact”. Frankly, we must cautiously ask ourselves what are these facts that we should accept? As readers and students of history we should look for histories that have legitimate factual sources but also pull a deeper wisdom out of the results of the changes they’ve presented.

“’Nobody can abolish the past’”- F.M. Powicke (Southgate, pg. 134)

Purpose and Goal

Indeed the establishment of historical fact is out there, but historians continue to express a continued quest to find no meaning in unyielding research. By questioning meaning we internalize a deeper, profound message from the lessons of the past. The purpose of postmodernist history is not allow baseless revisionism but to simply change the relation of history to the purpose of its end goal. This incites the usage of narrative within historical literature. The basic structure of storytelling is the cornerstone of historical research, it forces the historian to accept the need to put together purpose for the reader.

The goal of postmodernists is to understand the deeper implementation of the narrative within history, the realization that meaning goes beyond the literal facts that the author hopes to share. It remains the perpetual goal of the historians to give the reader that sense of purpose in history. The mindful nature of interpretation is forefront in goal of the historian and the challenge against old forms of “objective” interpretation is now more valid than ever. The meaning imparted from such interpretation, must guide the reader the basic framework of the past a way that pulls meaning from historical narrative long thought to have been settled. If for no other reason, this quest for meaning guides in a search relatable realism in our histories. That realism, which is too often overlooked as near nihilist examination of pointless histories, should be reexamined as an attempt to give an individualized truth for each student to experience. (Southgate, pg.136-7)

‘Do not ask who I am and do not ask me to remain the same … Let us leave it to our bureaucrats and our police to see that our papers are in order’. – Foucault (Gutting, pg.1)

The meaning of the histories we write take on their own life in a manner that can never be objectively pinned down. Instead the historian should see the work as a method to propose meaning. It can be a terrifying prospect to accept strict objective historical facts have no accurate meaning. But we should reveal in the challenge of exploring the narrative historians are presenting before you. The nature of our world is too often blindly accept the reality we’ve become easily socialized to. Regardless of Foucault’s critics, he teaches us to step outside of what we perceive as the truth. He implores to ask question of society and how the world has been complacent with itself.

Conclusion

We must question ourselves, not to uproot our own code of values and reality, but to understand why we believe the way we do. What decisions of influences lead to us to understand our past, present, and future? Just within ourselves we must exploring a deeper cause to our actions, how can we write history without internally doing the same. Causation is not simple in human behavior and if we are to relate ourselves to the past we must also see how the past relates to our present. The postmodernist struggle in history is not one that ends in the formless pit in the swamp of misery, but an open causeway of endless paths that implore us to explore. If one is concerned that anything is pointless, then reveal in the obscurity. For history gives comfort in knowing that never has humanity set to achieve what we have achieved, but that in the struggle for purpose and meaning have carved the way for a future of hope.

Bibliography

Breisach, Ernst. On the Future of History: The Postmodernist Challenge and Its Aftermath. Acls Humanities E-Book. University of Chicago Press, 2003.

Carole Turbin, author. “Introduction to Roundtable: What Social History Can Learn from Postmodernism, and Vice Versa? Or, Social Science Historians and Postmodernists Can Be Friends.” Social Science History, no. 1 (1998): 1.

Foucault, Michel. The Archeology of Knowledge. London: Routledge, 1989.

Foucault, Michel, and David Couzens Hoy. Foucault : A Critical Reader. Oxford, UK ; New York, NY, USA : B. Blackwell, 1986., 1986.

Gura, Judith, and Charles Jencks. Postmodern Design Complete. London : Thames & Hudson, 2017., 2017.

Gutting, Gary. Foucault : A Very Short Introduction. Very Short Introductions. Oxford : Oxford University Press, UK, 2005., 2005. http://libproxy.unm.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cat06111a&AN=unm.EBC422593&site=eds-live&scope=site. Mari, Giovanni. Postmodern, Democracy, History. Aurora : The Davies Group, Publishers, 2006., 2006.

Munslow, Alun. Deconstructing History. New York NY : Routledge, 2006., 2006.

O’Leary, Timothy. Foucault : The Art of Ethics. London ; New York : Continuum, 2002., 2002.

Phillips, Jason. Storytelling, History, and the Postmodern South. Southern Literary Studies. Baton Rouge : Louisiana State University Press, 2013., 2013.

Rüsen, Jörn. History : Narration, Interpretation, Orientation. New Approaches to Cultural History: 2. New York : Berghahn Books, 2004., 2004.

Southgate, Beverley. Postmodernism in History : Fear or Freedom? London : Taylor and Francis, 2003., 2003. http://libproxy.unm.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cat06111a&AN=unm.EBC180915&site=eds-live&scope=site.

Wesseling, Elisabeth. Writing History as a Prophet : Postmodernist Innovations of the Historical Novel. Utrecht Publications in General and Comparative Literature: V.26. Amsterdam : John Benjamins Publishing Company, 1991., 1991. Green, Anna, and Kathleen Troup. The Houses of History: A Critical Reader in History and Theory. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2016.

Jenkins, Keith. The Postmodern History Reader. London: Routledge, 2006.

MUNSLOW, ALUN. NARRATIVE AND HISTORY. S.l.: PALGRAVE, 2018.

Southgate, Beverley. What Is History For?London: Routledge, 2005.

2373 words.