Postcolonialism

What is Postcolonialism and Why Should We Care?

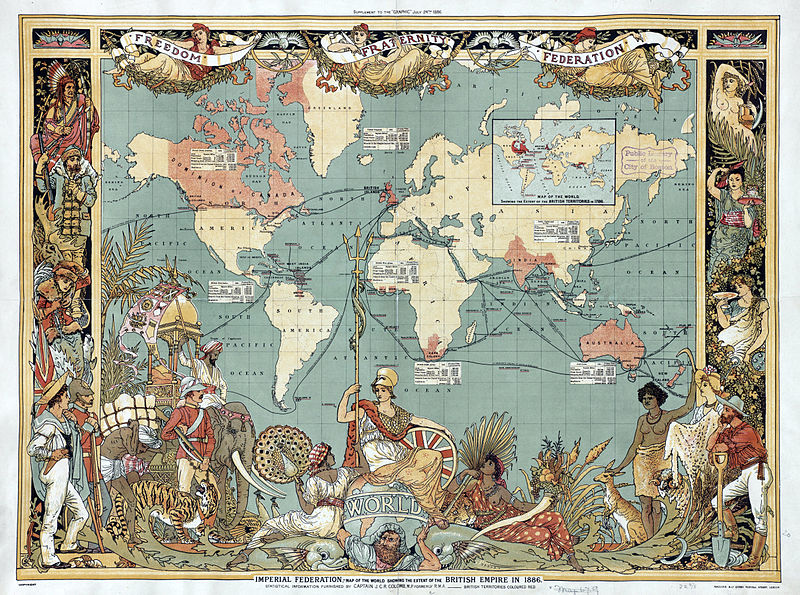

Postcolonialist history is part of the larger umbrella of poststructuralist historiography, a type of historiography based on the idea that history, or knowledge in general, cannot reach a single, objective truth. Postcolonialism is a school of thought that deals with the effects of colonization on societies and peoples. The term “Postcolonialism” is a bit of a misnomer— ‘post’ typically means ‘after’, which implies that Colonialism has ended and the study of it takes place afterwards (McClintock, 259). However, the societies examined through the lens of Postcolonialism are still dealing with many of the problems of colonization such as the struggle for independence, return of resources, and recovery of history (Houses 278). However, the eurocentric view of history, the one in which Europe remains at the center of culture and society, views colonialism as firmly in the past. In that perspective, colonialism was an integral part of capitalist development in the West, where the colonies were used as resources for raw materials to fuel production. Rather than focus on how colonialism affected the societies that were colonized, it upholds colonialism as part of the “European grand narrative of modernization,” or a period of history in which the key defining feature was the modernization in the West despite the many peoples who were conquered and subjugated (Chatterjee, xi).

In order to address Postcolonialism, Postcolonialist historians first address how Colonialist historians created their narratives. During colonization, histories were largely written by the elite European conquerors. The eurocentric worldview of these conquerors led them to write histories of the societies they colonized in a manner that placed them relative to European societies. Furthermore, the colonists placed the peoples they colonized both as diametrically opposite of their own and lesser than, allowing them to justify treating them as subordinates.

The writing of Postcolonialist histories is an effort to counteract the lasting effects of the colonial histories, which tend to ignore or gloss over the severe damage colonialism has had on society. This includes the loss of land and resources, which hold significant spiritual and economic value. Cultural traditions and knowledge of pre-colonial pasts have also been wiped out in many places, due to persecution and forced conversions.

We can look to the Spanish conquest of the present-day American Southwest for evidence of the consequences of colonialism. Indigenous peoples not killed by foreign diseases or war were often captured and forcibly converted to Christianity. The Conquistadores employed extreme violence in their takeover of the American Southwest and Mexico, resulting in deaths of countless indigenous peoples (Restall, 96), but colonial history typically does not spend time addressing the negative consequences of their exploits. This causes issues in their narrative writing. Often, the losses indigenous peoples suffered are missing from the narrative, which produces a version of history in which these people’s voices and experiences are excluded. In trying to correct these issues, “[p]ostcolonial historical writing… has developed [the] two critiques of imperialism and colonialism by deconstructing colonialist discourses, and reconstructing the appalling scale of loss experienced by colonized and indigenous peoples” (Houses, 281).

Postcolonial historical writing is an attempt to move away from imperialist and colonial views of societies and return to Enlightenment ideals and portray the impact of colonialism on colonized societies in a more honest and thorough manner. According to “The Postcolonial Aura,” one of the goals of postcolonial writing is to reestablish colonized societies as complex and nuanced, rather than in the simplistic ways they are presented in colonial histories (329). To accomplish this, two different schools of thought were developed in writing postcolonial history: essentialism and the subaltern approach.

Essentialism

Essentialism is the idea that the only real way to combat colonial ideas is to return to pre-colonization ideals and culture (Houses, 282). This is especially important in the discovery of land rights. For example, “historians in [colonized] countries play a key role in reconstructing the historical process of land alienation” (Houses 278-9). Presenting a narrative that clearly outlines pre-colonization ownership of land and resources is a valuable tool for these peoples, because it can help them in political and legal battles with colonizing forces over land ownership claims. By having a record of what was taken from them, they can use it in their efforts to “decolonize” ancestral lands and resources in their fight for independence.

We see this frequently in the Southwest United States, where the indigenous peoples continue to struggled with the United States government and private corporations for possession of sovereign, protected, and ancestral lands. The struggle between the United States government and indigenous Americans over the recent shrinking of Bear’s Ears National Monument for natural resource extraction (US National Forest Service) is one contemporary example of how the colonialist narrative is still playing out. Much of the land that was just removed from national protection is considered ancestral land by indigenous groups, and the removal of resources is considered a form of desecration. Looking at this issue through the lens of essentialism is one way to analyze the deeper causes and implications of colonialism.

The Subaltern Approach

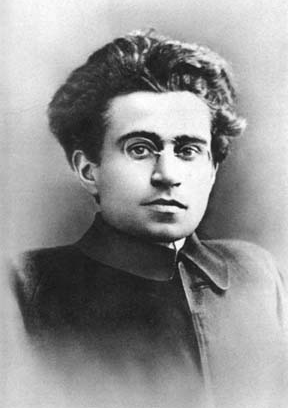

First laid out by Italian neo-Marxist philosopher Antonio Gramsci, the Subaltern approach reexamines colonialism through modern scientific methods like research and study. Where history was written from the perspective of a small elite class during colonialism, the Subaltern approach aims to rewrite it from multiple perspectives, including the perspectives of the subjugated peoples (Houses, 283). In this method, representation is a key concern.

By writing from a series of perspectives, rather than the limited, Eurocentric one, history can be presented in a more universal light. In other words, history becomes more inclusive and avoids a single narrative in an effort to find deeper truths within the often conflicting accounts. One of the ways the subaltern approach addresses this issue is by critically engaging problematic ideologies like nationalism (Houses, 284). These ideologies tend to rely on biased narratives and the “othering” of external groups, like colonized peoples. They present a narrative that upholds those in power, justifying thier actions through the guise of “progress” or “modernization.” Anyone outside these narratives becomes villainized because they are then fighting against the advancement of those in power.

Essentialism and Subaltern Methods in Action

Essentialist post-colonial history focuses more on pre-colonization history more than anything else. This distinction defines their history’s purpose as returning the colonized society to pre-colonized ways. This can take the form of fighting for the restoration of land, the revitalization of an indigenous language, or the resurgence of pre-colonial religions, foods, or fashions. In histories written with the Subaltern method, the focus is on the ignored voices of colonial history, which then leads to a purpose of directly addressing the problems of colonialist historical writing. The use of modern methods to attempt to reach a more accurate version of history lends this type of postcolonial writing to teaching and education. It fills a corrective role in society, where the narrative it produces reveals neglected facts and corrects the Eurocentric bias of colonialism. The subaltern approach advocates rewriting of colonial histories but also begs the question of who can write them. What role does authorship play in determining how trustworthy these histories are?

Possessive Exclusivism and Questions of Authorship

The academic world is split on the issue of whether it is possible, let alone acceptable, for a historian from outside of a colonized society to write a postcolonial history. Some within colonized societies find this idea inappropriate. Some cultures in the Western world, in areas like North America and the Pacific, subscribe to “possessive exclusivism”, or the idea that only the colonized should write postcolonial history (Houses, 282). This idea tends to go hand in hand with the essentialist idea of writing history. If the goal of the history is to provide a narrative that restores pre-colonial power in some way to colonized peoples, the concern over whether or not an outsider is writing the narrative is key. If the narrative comes from within the society, it is an act of empowerment. If it is written by an outsider, it can come across as yet another external group trying to control what the colonized society does.

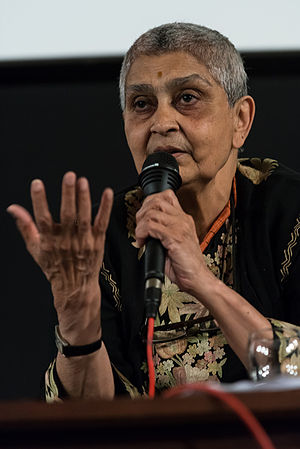

Other areas of the academic community see no problem with historians with outside perspectives writing postcolonial histories. In “Questions of Multi-culturalism,” author Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak argues to this end (62-3). Histories of this inclination tend to align themselves more with the perspective that postcolonial history should be written with subaltern methods. Because the subaltern type of postcolonialism is not necessarily geared towards returning colonized peoples to their pre-colonial pasts, it is less important what the historian’s personal background is. What is more important is how they deal with their personal biases. While it is impossible to ever write a completely unbiased history, it is still important for historians writing postcolonial history to be aware of their own biases and not allow them to interfere in their narrative. For this type of postcolonial narrative, the question of who writes it is not nearly as important as if it is written fairly or not.

Questions of Evidence

Regardless of the chosen methods or intent of writing a postcolonial narrative, postcolonial history all aims to do one thing: rewrite colonial history to give a voice to the groups that were underserved and unacknowledged in colonial history. This goal has its challenges; the biggest one being that sometimes it is impossible to create a true postcolonial narrative at all. This challenge comes from the current expectation that historical narratives should be created from traditional Western evidence i.e. firsthand accounts, provable facts, and written sources. Writing postcolonial history is challenging because these types of sources are often heavily biased towards a Eurocentric ideal, or historical evidence simply does not exist in a way that would be easily converted into a modern narrative (Houses, 284-5). For example, oral history constantly changes, purely by the nature of its distribution. It is extremely difficult to find concrete evidence within evolving oral histories that can be scientifically tried and tested. In other cases, history was deliberately erased by colonizers. In cases of conversion, traditions and stories are deliberately replaced by the traditions of the colonizers, like the modification of holidays to better suit the new religion. Because of this, writing true postcolonial histories is sometimes impossible, because concrete evidence is sparse or has been modified so heavily it is no longer trustworthy.

Conclusion

There is no singular approach to postcolonialism. Essentialism and the Subaltern method should not be compared to each other in terms of which is more effective, because each one aims to accomplish different goals within postcolonialism. The essentialist approach seeks to reestablish what societies ideally should be, by focusing on the historical narrative of what life was like before colonization. The subaltern method looks to interact directly with colonial narratives to expose the negative effects of colonization not addressed in earlier histories. Postcolonial historical writing can pick up where colonial historical narratives fall short. Whether using the essentialist or subaltern approach, postcolonialism engages with colonialist histories in an attempt to address their faults and produce narratives more focussed on human value.

Consider This

- What histories have you been told from the colonialist perspective?

- How have those narratives changed the way you view the world and your place in it?

</figure>

- Do you support the idea of possessive exclusivism?

- Do you have histories that are personally significant that should not be told from an outside perspective?

- Should historians continue to value written sources over other types of evidence such as oral histories and folklore?

- Is one particular history more true because we have records of it in an archive?

Want to Know More?

The last couple of generations have produced some incredible works in postcolonial thought. Check out some of these great authors if you want to delve more into postcolonial history:

Sources

Armitage, David. 2007. “From Colonial History to Postcolonial History: A Turn Too Far?” The William and Mary Quarterly 64 (2): 251–54.

Ashcroft, Bill, Gareth Griffiths, and Helen Tiffin. 1994. Post-Colonial Studies Reader. London, Unknown: Routledge. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/unm/detail.action?docID=3060300.

Chakrabarty, Dipesh. 1992. “Postcoloniality and the Artifice of History: Who Speaks for ‘Indian’ Pasts?” Representations, no. 37: 1–26. https://doi.org/10.2307/2928652.

Chatterjee, Partha. 1993. The Nation and Its Fragments : Colonial and Postcolonial Histories. Princeton Studies in Culture/Power/History. Princeton, N.J. : Princeton University Press, ©1993. http://libproxy.unm.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cat05987a&AN=unm.27934680&site=eds-live&scope=site.

Dasgupta, Subrata. 2014. “Science Studies ‘sans’ Science: Two Cautionary Postcolonial Tales.” Social Scientist 42 (5/6): 43–61.

Dirlik, Arif. 1997. The Postcolonial Aura: Third World Criticism in the Age of Global Capitalism.

Green, Anna, and Kathleen Troup. 1999. The Houses of History : A Critical Reader in Twentieth-Century History and Theory. New York : New York University Press, 1999.

Krishna, Sankaran. 2008. Globalization and Postcoloniailism: Hegemony and Resistance in the Twenty-First Century. Blue Ridge Summit, United States: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/unm/detail.action?docID=500871.

McClintock, Anne. 1992. “The Angel of Progress: Pitfalls of the Term ‘Post-Colonialism.’” Social Text, no. 31/32: 84. https://doi.org/10.2307/466219.

| “News Release | US Forest Service.” 2018. 2018. https://www.fs.fed.us/visit/secretaries-jewell-vilsack-applaud-designation-new-national-monuments-utah-nevada. |

“Postcoloniality and the Two Sites of Historicity.” 2017. History and Theory 56 (1): 38–53.

Restall, Matthew, and Felipe Fernandez-Armesto. 2011. “The Conquistadors: A Very Short Introduction.” 2011. https://eds.b.ebscohost.com/eds/ebookviewer/ebook/bmxlYmtfXzQxNDQxMV9fQU41?sid=ae36af0b-b2f0-4613-90ad-591f1381d627@sessionmgr103&vid=1&format=EB&rid=4.

Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty, and Sarah Harasym. 1990. The Post-Colonial Critic : Interviews, Strategies, Dialogues. New York : Routledge, ©1990. http://libproxy.unm.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cat05987a&AN=unm.22192413&site=eds-live&scope=site.

“Writing Postcolonial History / Rochona Majumdar.” n.d.

2411 words.