Professional History

The legacy of Leopold Von Ranke

In mid-nineteenth century Germany, a professor at the University of Berlin would fundamentally change the way history is taught and applied. No individual contributed more to the professionalization of historiography than Leopold Von Ranke. Ranke’s historical methods would become a mainstay on the modern college campus (Cheng, 2012, p. 92). Ranke’s implementation of the modern seminar system, peer review, source critique, and objectivity cumulated in a general practice on how to conduct historical study. Before Ranke, there was no standardized methodology, historians utilized their own rudimentary approaches. While methodologies changed, and many accept the shortcomings and hypocrisy of the man himself, Ranke’s contributions to the professionalization of history cannot be disregarded.

Before the mid-nineteenth century, historians conducted their work as a hobby or as a part of literature or philosophy; the idea of being a historian on its own merit was absurd to most people in academic environments. Ranke bridged this gap through the application of scientific methodologies that brought the idea of history as an academic practice to fruition. Ranke’s scientific historiography focused on four main principles (Gil, 2009, p. 384-385):

- objectivity and a rejection of moral lessons

- trusting the facts over all else

- seeing historical events for their uniqueness (divergence over similarity)

- maintaining impartiality when referencing political works

If asked to sum this up, Ranke would declare that history is “documentary, not speculative” (Gil, 2009, p. 385). To Ranke, any evidence that was not empirical should not be considered. Historian Emile Benveniste articulated Ranke’s beliefs in this statement: “I wish I could annihilate my own self and only the objects would speak” (Maurer, 2006, p. 315). Ranke’s vision of a perfect historian entails a mere collection of sources, with no evident personal bias. This is a stark contrast from previous historical works, and the first real alternative to the ancient standard that was set by the famous Greek historian, Thucydides (Muir, 1987, p. 3). Beforehand, historians would still justify their writings with source material, but the sheer level of empirical research that the Rankean Method requires is much more intensive than what was previously completed. Ranke’s shift required historians to be accountable for their narratives who now had to back their work with real, empirical sources.

Ranke first brought his methodology to the University of Berlin (Torstendahl, 2014, p. 43). By the late nineteenth century, these principles of professionalization were fully integrated into western academia. Ranke was also the first historian to be recognized for his contributions as a professor, not merely as a historian (Popkin, 2016, p. 76). This led to the practice of historians becoming respected academic celebrities. The sheer popularity of future historians such as Marc Bloch and Michael Foucault can be attributed to Ranke making the historian a valued position in society. While historians of the past certainly have achieved similar fame, it was never for their contributions to academia.

Ranke certainly emphasized a focus on objectivity, but his principal ideaology was the “pure love of truth” (Ranke, 2010, p. 39). The professionalization of history meant the value of truth should be placed above all else to a historian. Before this turn to scientism “the skill of historians was… their linguistic forms… it [the historian] was guided by the principles of addressing an audience, by speaking to someone; it was indeed rhetorical” (Rüsen, 1990, p. 192). Rhetoric was a historian’s primary contribution before Ranke. One’s ability to captivate an audience of their goal, whether it be moral lessons or a political agenda, was paramount. Roman and Renaissance historiographers acknowledged the important role rhetoric had in their methodology. Ranke believed such work to be crude and unprofessional as “such sentiments made history a branch of moral philosophy where rhetorical form and ethical maxims subordinated the pursuit of simple accuracy” (Muir, 1987, p. 4). Ranke did not believe that historians should judge the past and make moral assumptions(Gil, 2009, p. 384; Popkin, 2016, p. 76) but rather, by eliminating rhetoric in their works and embracing pure empiricism, historians believed they could achieve this pure love of truth that Ranke envisioned.

Only recognizing empirical evidence as acceptable source material led Ranke to incorporate peer review in his classes. Peer review was conducted through Ranke’s seminar system. Before Ranke, history was taught primarily in lecture series. History students were given a narrative but had no instruction on how to create their own. Ranke saw this flaw in history education and created smaller, interpersonal classes where students sat in groups and subjected their works and opinions to criticism from fellow pupils. Historically-inclined peers now determined the success of a historical narrative, not the public or a ruling class (Popkin, 2016, p. 79). Historians saw this change as improving the objectivity of their research; by not having to adhere to any one figure or community’s personal desires, the historian could write about the unfiltered truth. Even in a modern context, post-graduate history courses are still conducted by the seminar guidelines that Ranke enacted in his classrooms.

Proliferation of history as an academic pursuit formed a stark shift in how historical writing was conducted. While previous historians often looked for absolute truth or relied on religious or philosophical certainties, historians under Ranke knew that to achieve truth, it meant “not only establishing the facts as correctly as possible, but also placing them in their cotemporary context in such a way that the past would come to life again” (Gilbert, 1987, p. 394). German historian Friedrich Meinecke believed that this line of thinking would put all of history in a new perspective, as the “outcome of events is not determined by general laws that human beings cannot alter” (Popkin, 2016, p. 69). The legitimacy of historical work conducted in the past was put into question, as religious or moral lessons found in past historical works certainly breached the ideal of objectivity. This uneasiness in relying on past sources created an environment where “the entire history of the past suddenly cried out to be rewritten” (Popkin, 2016, p. 76). British Conservative Edmund Burke believed that these past histories should still be respected, as they are a “better guide for the present than rational maxims” (Popkin, 2016, p. 72). While historians still cite ancient Greek historians, such as Herodotus or Polybius, these source’s motives and bias must be called to question. Many historians still respect their traditions and acknowledge these past works for their practical experience but have garnered a healthy amount of skepticism when it comes to the reliability of these sources. This skepticism made some historians such as Foucault question source reliability even further, later cumulating into the postmodernist movement of the late-20th century.

.jpg)

Professionalization meant that there were more individuals proclaiming to be historians than ever before. There was now a group of like-minded peers who shared in the same pursuits, occupied similar positions in society, and conceptualized identical limitations of their work. These individuals created a “new sense of collective identity soon led to the formation of a professional organization whose function was to define a common standard of occupational conduct” (Hamerow, 1986, p. 320). Due to this, several organizations came into fruition and at the forefront of academic standardization, such as the United States American Historical Review. These organizations set high standards for academic historical work, putting increased emphasis on source material. This new concern for sources led to a revolution in how documents are preserved and accounted for. Professional archives exploded in popularity, giving historians a much larger pool of sources to draw from (Popkin, 2016, p. 80). The American Historical Reviews first editor J. Franklin Jameson played a crucial role in “the professionalization of history by using the journal to establish uniform standards of scholarship” (Cheng, 2012, p. 96). As first student to graduate with a Ph.D. in history from John Hopkins University (one of the first American Universities to adopt a Rankean seminar program), Jameson built upon Ranke’s approach, adding that while historians should attempt to be objective, they could never truly be. This idea would later be expanded upon in the 20th century, with the Annales school of thought and other historians that believed Ranke’s ideals to be naïve and impossible to achieve.

As with any approach to history, there are drawbacks to Ranke’s methods. In the seminar classroom, oral histories were discredited as unreliable due to a lack of empirical evidence. While historians often only wrote of their own country in this nationalistic period, this trend only gave credit to the notion of non-empirical history (read: non-western history) being unreliable at best. The common ideal of the era was that historians should be non-biased in their work. As seen in later essays of this collection, the modern consensus is that this is impossible. The action of picking sources automatically raises bias in a narrative, as choosing to include or exclude any source is an act of subjectivity (Iggers, Historiography in the 20th century, 2005, p. 470). Another negative aspect of professionalization was that generally only white males were accepted into history programs at universities. History continued to be male dominated and Caucasian-centric endeavor, as it had been since the creation of historical study and as it would be until the Annales and feminist movements of the 20th century. For decades “female historians were barred from publishing in major journals… as were African-American authors in the American Historical Review” (Lingelbach, 2011, p. 85). For more information concerning gender in historiography, please see gender pre-20th century.

Focusing on objectiveness created a tendency to rely on political source material. While Ranke did not discredit social and economic factors “in his works, they were seen and located in the framework of a political history (Gil, 2009, p. 385). It makes sense to use the most credited sources, but a focus on political documents “singled out documents that were generated primarily by the states” (Iggers, Historiography in the 20th century, 2005, p. 470). This was a contributing factor to the rise in nationalism in the 19th and early 20th century, nearly all history being taught at the academic level was political. Due to this trend, the modern political system utilized historians as propaganda machines during World War I/II, and even into the Cold War.

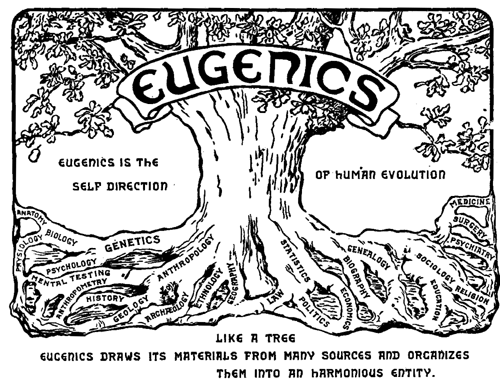

Another dangerous result of applying scientific methodology to history was the rise of narratives concerning racial purity and eugenics. These “racial explanations were frequently advanced to justify historical developments such as European imperial conquests in the rest of the world, the westward expansion of the United States, and slavery and segregation in the American South” (Popkin, 2016, p. 88). This became a rampant feature of this time, which coupled with nationalist ideals to a devastating effect in the late 19th and early 20th century. Even though Ranke vehemently opposed the concept of a “total” or “grand” narrative that encompasses all of humanity, he was often guilty of constructing these overarching narratives anyway (Popkin, 2016, p. 82). This highlights a reoccurring theme during this period, the hypocrisy of the Rankean historian.

.jpg)

Proliferation of nationalist historical works during this time can be attributed to the overall rising nationalist tendencies in the Western World but also, to the newly academic setting of history providing an avenue to partake in such narratives. German universities pushed nationalist narratives in their classrooms, due to the formation of the unified Germanic state that occurred during this time (Popkin, 2016, p. 70). Even Ranke contributed to German nationalism in his works, betraying his ideal of objectivity. Ranke asserted that “above all, [history] should benefit the nation to which we long and without which our studies would not even exist” (Ranke, 2010, p. 59). This would seem to contrast goes against his ideals of objectivity. Some even questioned his reasonings for adhering to pure truth. Georg G Iggers, a historian known for his work on historiography and Ranke specifically, believed that “this ideal of objectivity had been merely an outgrowth of the German ruling classes, with which Ranke was affiliated, directed at consolidating their position” (Iggers, The Image of Ranke in American and German Historical Thought, 1962, p. 25).

While it came with its own faults and was quickly criticized by the next generation of historians, Ranke and his methods paved the way for professionalism in history and allowed these historians an avenue to have their passion become a seriously considered profession. No individual had a greater impact on making history an academic pursuit more than Ranke. No name is more associated with the “scientific” turn of history. Ranke knew the importance of distinguishing history and fiction and set out clear guidelines that professionalized how history is conducted.

Works Cited

Cheng, Eileen Ka-May. “Historiography An Introductory Guide,” 91–111. Continuum International, n.d.

Gil, Thomas. “Leopold Ranke.” In A Companion to the Philosophy of History and Historiography, 383–92, 2009.

Gilbert, Felix. “HISTORIOGRAPHY: What Ranke Meant.” The American Scholar 56, no. 3 (1987): 393–97. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41211442.

Hamerow, Theodore S. “The Professionalization of Historical Learning.” Reviews in American History 14, no. 3 (1986): 319–33. https://doi.org/10.2307/2702604.

Iggers, Georg G. “Historiography in the Twentieth Century.” History and Theory 44 (2005): 8. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3590829.

“The Image of Ranke in American and German Historical Thought.” History and Theory 2, no. 1 (1962): 17–40. https://doi.org/10.2307/2504333.

Lingelbach, Gabriele. “The Institutionalization and Professionalization of History in Europe and the United States.” In The Oxford History of Historical Writing: Volume 4: 1800-1945, 4:72–96. Oxford University Press, 2011. https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=Ola8wEnMoM8C&oi=fnd&pg=PA78&dq=professionalization+of+history+&ots=1HIaMH23u5&sig=RSYQvpgs42EZ7IpejhqArldXUro#v=onepage&q=professionalization%20of%20history&f=false.

Maurer, Kathrin. “The Rhetoric of Literary Realism in Leopold von Ranke’s Historiography.” Clio (Fort Wayne, Ind.) 35, no. 3 (2006). https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?authtype=ip,guest&custid=s4858255&groupid=main&profile=eds&direct=true&db=hlh&AN=22350041&site=eds-live&scope=site.

Muir, Edward. “Leopold von Ranke, His Library, and the Shaping of Historical Evidence.” Syracuse University Library Associates Courier, 1987, 11. https://surface.syr.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1212&context=libassoc.

Popkin, Jeremy D. From Herodotus to H-Net : The Story of Historiography. New York ; Oxford : Oxford University Press, [2016], 2016.

Ranke, Leopold Von. The Theory and Practice of History: Edited with an Introduction by Georg G. Iggers. Taylor & Francis, 2010.

Rüsen, Jörn. “Rhetoric and Aesthetics of History: Leopold von Ranke.” History and Theory 29, no. 2 (1990): 190–204. https://doi.org/10.2307/2505225.

Southgate, Beverley. What Is History For? Routledge, 2005.

Torstendahl, Rolf. The Rise and Propagation of Historical Professionalism. Routledge, 2014. https://books.google.com/books?id=uilHBAAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false.

Wright, Donald A. The Professionalization of History in English Canada. University of Toronto Press, 2005. https://books.google.com/books?id=twzNaZ4VYCoC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false.

2497 words.