The Historical Significance of Marxism

Looking at the historical and political events of our lifetime, socialism has become inextricably ingrained in our lives at nearly every conceivable level and turn. The rise of this phenomenon can be squarely attributed to one man: Karl Marx. With the publication of the Manifesto of the Communist Party (1848), Marx laid the groundwork for a radical new view of the world and man’s interaction within it. First, an examination of the history preceding Marx and his work is needed to better understand the nature and significance of his vision and later effects on Europe.

The Enlightenment - Giving Birth to Social Change

With the arrival of the Enlightenment, Europe entered a new age: an age of growing science, art, and history. Prior to the Enlightenment, histories were largely focused on the documentation and discussion of royalty and religious figures.[1] As reason and scientific observation became central to the study of the natural world, the stranglehold of the Catholic Church as the sole authority on the history of mankind was deconstructed.

With Enlightenment, Europe experienced the growth of industrialization and the emergence of economic dependence on an international scale. Past methods of craft production were being replaced with the factories capable of mass-producing goods, expanding the economic reach of industrializing nations and the rise of capitalism. Consequently, the growth of industrialization was accompanied by the expansion of class divisions.

As class differences became more pronounced, the interpretation of history dramatically shifted and historians focused more on the social and economic disparities to which industrialization had given rise. In reaction to the increasing class divide of the 19th century, Marxism emerged as a means to represent the disadvantaged masses.[2]

The Rise of Marxism

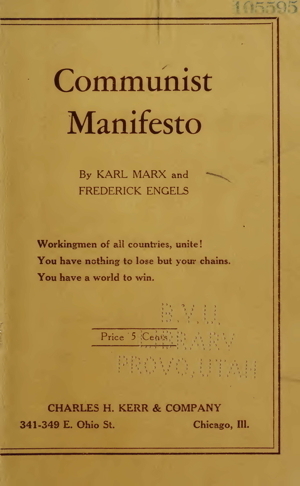

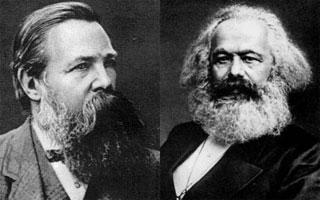

Marxism was a paradigm shift in the understanding of labor and economics. It is important to understand the mind behind this shift, Karl Marx. Working with his contemporary, Friedrich Engles, came the creation of the Manifesto of the Communist Party[3]. A product of mid-19th century social and economic discord, this work provided a theoretical and practical program for the establishment and growth of the Communist Party in Europe. Its purpose was to reflect on “the history of the modern working class.”[4] The ultimate goal of the working class was to shift the balance of power in their favor by gaining control of the economic and political systems.[5] Thus, Marx’s Manifesto was pivotal to initiating social and economic change.

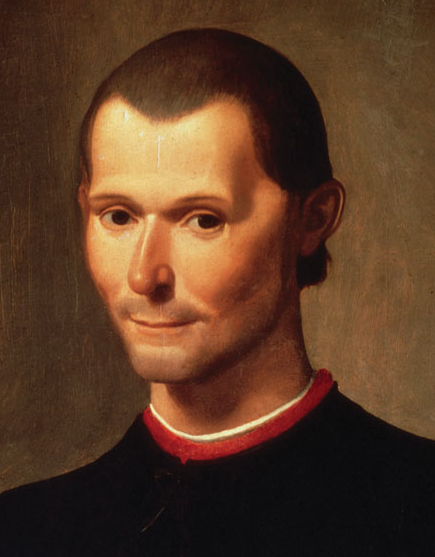

Social and class distinctions were nothing new in European history. Marx and Engles admitted there has always been a class that has been subservient to another since the Roman Empire.[6] Where the early Enlightenment author Niccolò Machiavelli focused on the Italian power struggles while presenting the perspective of the common people as instrumental in maintaining power, Marx was convicted to the importance of the working class in building and sustaining the health of society.[7] This ideal extended to full integration and involvement in the political and economic machines at every level by those most responsible for their success, the workers.

Marx emphasized the Industrial Revolution as seminal in the rise of social and economic inequalities. E.P. Thompson mentions in Exploitation, “The physical instruments of production were seen as giving rise in a direct and more-or-less compulsive way to new social relationships, institutions, and cultural modes.”[8] Marx continues, “Modern industry has converted the little workshop of the patriarchal master into the great factory of the industrial capitalists.”[9] The decline of the aristocracy gave rise to two classes, according to Marx: controlling capital and the means of production were the Bourgeoisie[10], and the exploited workers, subordinate to the capitalist Bourgeoisie, were the Proletariat”.[11] Marx had identified the largely overlooked actors in previous historical writings.

Class Divisions

With two distinct classes identified, Marxist historians specifically focused on the lives of the workers. The plight of the worker has been described as an uneasy relationship between the worker and the manufacturer. Employers dominate their enterprise, maximizing profits by controlling access to the means of production and employment, depressing wages, and subduing the moral of the working-class proletariat. The workers’ fight must keep their jobs to obtain the fulfill their needs including food, clothing, and shelter according to Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs[12]. Unable to quit, workers feared economic isolation. Ultimately they submit to capitalist demands and endure their tragic abuse,[13] victims of the emerging yet perpetual industrial system. An injustice, the economic system was one from which the worker could not escape.

The factory was an iconic symbol of oppression, providing a glimpse into the working conditions of 19th Century England. The factory housed dreadful working conditions attributed to the increase of manufacture, rising population in the cities, technological innovation, and capitalist profiteering.[14] Factory conditions were worse than those experienced by plantation slaves in the American South.[15] Slaves worked largely an open-air environment; factory workers labored in hot and unventilated rooms for hours with little or no rest.[16] With two distinct classes identified, Marxist historical writing centered on the workers’ plight and revealed to the world the economic and social disparities of the two classes.

Ideas Flourish and Spread

Influenced by the Enlightenment, Marxism was grounded in observation; the observation of class inequities. The French Revolution (1789) demonstrated that ordinary people were active participants of history and they were capable of controlling their own destiny.[17] Johannes Guttenberg’s printing press extended the distribution of written texts, making them more accessible to the masses.[18] Manifesto and its ideas captured the imagination of the oppressed, igniting discontent throughout Europe and across large swaths of the European-influenced world.[19] With the bourgeoisie in control of production and distribution, printed Marxist literature carried a heavily watered down the message. Later Marxist authors, including Vladimir Lenin, developed creative methods to expand the reach of their message, which included disguising their true meaning of messages.[20] The Marxist message reached an expanded audience, though the subversive message was diluted to escape 20th-century government censors.

Lenin Carries the Banner of Marxism

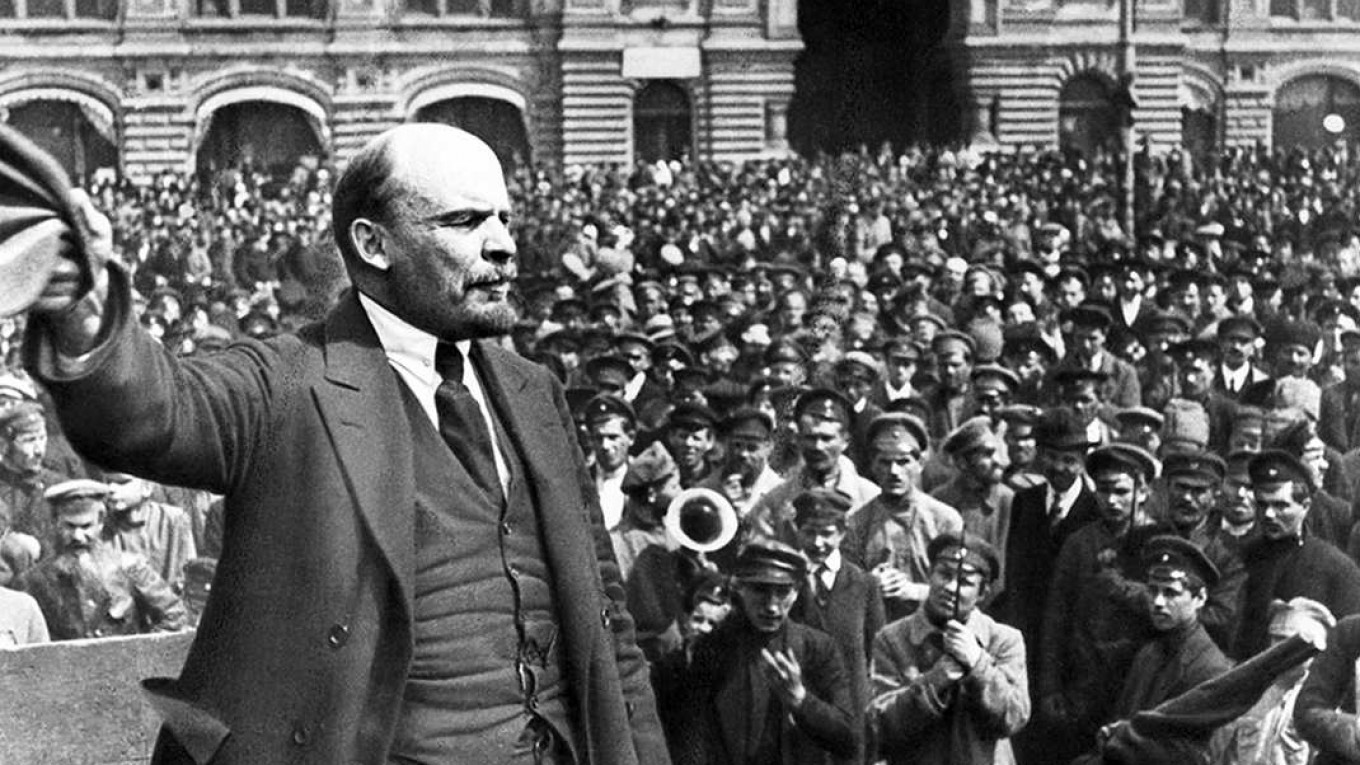

What made Vladimir Lenin unique in historiographical literature was his passion and dedication to the cause. “[N]o proposition is more susceptible of historical truth than that there is a tendency for various economic groups to become aware of their class interests and to work consciously for the fulfillment of ends which they consider good.”[21] In What is to be Done? (1913), Lenin states, “ [The] role of vanguard…can only be fulfilled only by a party that is guided by an advanced theory.”[22] His charisma, intelligence, and conviction were key to awakening the masses from their class ignorance.

Using an authoritative and condescending tone, Lenin’s work successfully incited the workers, trade unions, and peasants into class consciousness.[23] Captivating the imaginations of the oppressed, Lenin was successful inciting large segments of the ‘proletariat’[24] and cast the existing economic and class systems into turmoil, as Marx had proffered in The Manifesto.[25] The use of a commanding narrative by Lenin swayed his contemporaries into political action, altering the landscape of modern historiography. Western 20th Century historians like Gordon Watkins, Emile Vandervelde, and E.P. Thompson, have offered their perspectives and interpretations of Marxism, as we will see.

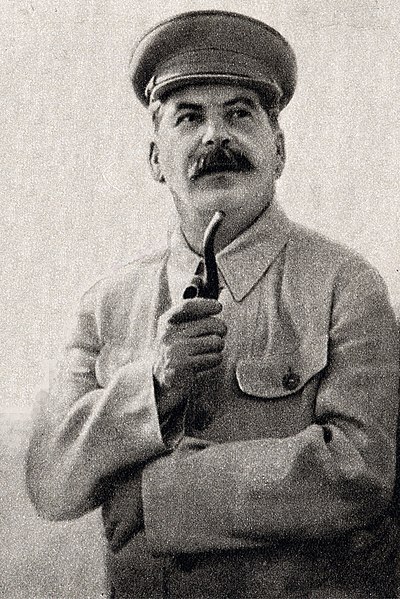

Stalin and Nationalism

During the Enlightenment, nationalism was on the rise as nations attempted to preserve their own cultures and distinct identities,[26] a subject on which Joseph Stalin was well versed. A disciple of Lenin and avid Marxist, Stalin was outspoken on the requirements of the nation-state. In Marxism and the National Question, he described nation-state as a

“historically constituted, stable community of people, formed on the basis of a common language, territory, economic life, and psychological make-up manifested in a common culture.”[27]

Stalin’s view was reflective of Marx and his definition of the various elements that comprise nation-states and their development throughout Europe.[28]

The Spread of Marxist Ideology

Russian Marxism literature eventually reached and inspired workers across Europe and the United States.[29] In 1919, 54,000 people voted for the Communist Party during the New York primary elections, Americans were aware of class disparities.[30] Emile Vandervelde argues in the Ten Years of Socialism in Europe,[31] that “Whether they have read a line of Marx or not, there is not a coal-miner in Yorkshire…who does not join with the social-democrats.”[32] Vandervelde’s writing indicates that each country will have its own historiographical writing and its own variety of Marxism[33]. The success of Marxism in some countries and its failure to gain traction in others can be attributed to Marx’s incomplete understanding of the cultural differences.

Western historians differ from their Eastern European colleagues in their views and interpretations as they are extremely critical of the utility of Marxism in Western capitalist society. Among those in opposition to their Eastern European counterparts is Gordon Watkin. In his work, “Revolutionary Communism in the United States” [34] Watkins is highly critical of Marxist politics in the U.S. He posits that about the function and structure, forecasting the forthcoming demise of Marxism in the United States.

Differing Ideas of Marxism

In Watkin’s time, there were two distinct Marxist parties within the country: The Socialist Party and Communist Party. The Socialist Party promoted economic change through political means. The Socialist Party encouraged its members to participate in voting, to seek appointment to an office within the bureaucratic machine, or election to expose Capitalist corruption.

The Communist Party decreed that change can only occur through violent revolution, like the Russian Revolution.[35] To do this, they needed help from the unions.[36] Their strategy was “the conquest of power in the industrial unions may become the starting point of the communist reconstruction of society.”[37]

Neither the Socialist nor the Communist parties could agree whether an economic and political change should be initiated by political intervention or violent struggle.[38] To Watkins, the American problem was simple, “[the] American workers are too prosperous to become susceptible to revolutionary political and industrial philosophy.”[39] As Marxism experienced success in Europe, the criticism received in the United States was vocal and vociferous.

The Shift and Its Implications

Marxism represented a paradigm shift in political and economic thought. Its rise was driven by poor working conditions and the inequitable treament of laborers. Setting it apart was its emphasis on social, economic, and political shifts caused by changing conditions stemming from industrialization. The movement was a great influence in the struggle against colonialism and imperialism.[40] With the increase of global trade, mass production, and political activism–more apparent in the 21st Century–Marxism is just as relevant today as it was in the 19th century.[41] In the “Problem with Historical Interpretation”, B.B. Kendrick mentions “[the] philosophers and the economist can teach us something about the interpretation of history, [they] can’t teach us everything.”[42]

With history, as with all things, timing is as influential as the message. Conditions had to be ripe for Marx’s message to gain attention and the movement to be successful. Technological advancements, political conditions, plus the deepening of social and economic divides fed the discontent of the working class and nourished Marx’s visions of the communist/socialist ascent. Marxism was indeed “revolutionary” for its time, a revolution that carries forward into today. The influence of Marx continues today with the message of social responsibility resonating throughout modern historiography and politics.

FOOTNOTES

[^1] Jeremy D. Popkin. “From Herodotus to H-Net: The Story of Historiography,” (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, [2016], 2016), 57.

[^2] Karl Marx and Frederick Engles. The Communist Manifesto. (International Publishers Co., 2014).

[^3] Manifesto of the Communist Party.

[^4] Karl Marx and Frederick Engles. The Manifesto of the Communist Party, trans. Samuel Moore with Frederick Engles. (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1969 [originally pub. 1848]), 8. https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/download/pdf/Manifesto.pdf. Accessed 17 September 2019.

[^5] Marx and Engles 2014, 30.

[^6] Marx and Engles 2014, 89; Marx and Engles 1969, 15, 54.

[^7] Niccolò Machiavelli. The Prince (with related documents). Edited by William J Connell, 2016.

[^8] E.B. Thompson. “Exploitation”, The Houses of History: A Critical Reader in Twentieth-Century History and Theory. (New York: New York University Press, 1999), 46.

[^9] Marx Engles 2014, 16.

[^10] Marx and Engles 2014, 10-11.

[^11] Thompson, ??.

[^12] Saul MacLeod. “Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs,” SimplyPsychology, updated 21 May 2018.

https://www.simplypsychology.org/maslow.html; Tom Rockmore. “Marx.” A Companion to the Philosophy of History and Historiography,(2009, 488–97), 490.

[^13] Thompson, 54.

[^14] Ibid., 47.

[^15] Ibid., 55.

[^16] Ibid., 55.

[^17] Popkin, 71.

[^18] Popkin, 53-54.

[^19] Vladimir I. Lenin. What Is to Be Done? [Burning Questions of Our Movement] (Martino Fine Books, 2013), 20-21.

[^20] Lenin, 20-21.

[^21] Marx and Engles 2014, 27.

[^22] Vladimir I. Lenin. Collected Works, Vol IV. trans Joe Fineberg and George Hanna, ed Victor Jerome. (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1977), 380. https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/cw/pdf/lenin-cw-vol-04.pdf. Accessed 22 September 2019.

[^23] Lenin, 28.

[^24] Ibid., 31-35.

[^25] Hal Draper. “The Principle of Self-Emancipation in Marx and Engels,” Socialist Register 1971, pp. 81–109.https://www.marxists.org/archive/draper/1971/xx/emancipation.html. Accessed on 22 September 2019.

[^26] Marx and Engles, 6, 20.

[^27] Popkin, 70.

[^28] Joseph Stalin. Marxism and the National Question (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2013), 12-13.

[^29] Marx and Engles, 20.

[^30] Gordon S. Watkins. “Revolutionary Communism in the United States.” American Political Science Review 14, no. 01 (February 1920, 14–33), 20. https://doi.org/10.2307/1945723.

[^31] Watkins, 14.

[^32] Emile Vandervelde. “Ten Years of Socialism in Europe.” Foreign Affairs 3, no. 4 (1925): 556-5??, 560. https://doi.org/10.2307/20028399.

[^33] Vandervelde, each country will have its own historiographical writing and its own variety of Marxism.

[^34] Watkins, 32-33.

[^35] Watkins, 20.

[^36] Ibid., 20.

[^37] Ibid., 26.

[^38] Ibid., 19.

[^39] Ibid., 14.

[^40] Anna Green and Kathleen Troup. The Houses of History: A Critical Reader in Twentieth-Century History and Theory (New York: New York University Press, 1999), 277-278.

[^41] Linden, Marcel van der. “The ‘Globalization’ of Labor and Working-Class History and Its Consequences.” International Labor and Working-Class History, no. 65 (2004), 136–56), 136-149.

[^42] B.B. Kendrick. “The Problem of Historical Interpretation.” The North Carolina Historical Review 2, no. 1 (1925): 19–29, 27.

2506 words.