Historiography of Elizabeth I

Queen Elizabeth the First of Britain was one of the most idealized, revered monarchs in European history. Ruling for 44 years, from 1558 to her death in 1603, she still stays on the list of top ten longest-ruling monarchs of the United Kingdom. Perhaps most impressively, she managed to accomplish this despite the fact that she was a woman. But how did historians think of her, throughout time?

Historiographically speaking, there has been very little attention paid to women before the modern era. There are, however, exceptions, a key one being the history of female regents, and other female members of royal families. The treatment of Queens like Elizabeth I, Victoria, Isabella, and Catherine the Great serve as indicators and influencers for the overall view of women in the public reckoning.

Queens, and other high-ranking women, unlike other women in our past, were actually written about by male historians before the rise of post-modernism in Historiography. This is what makes them interesting characters we can use to observe the general opinions towards women during the era in which historians wrote about them, as well as general barometers for their methodologies. Here we will look at three different biographies of Elizabeth I.

Each has a structure representative of the historical methodologies and philosophies of the era in which they were written. They each also have a common story, regardless of the focus of the biography itself: that of Elizabeth’s favorite, Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester. The different approaches to this story serve to further articulate their different eras of historiography, and for this reason we will examine them as well.

A Post-Renaissance, Pre-Enlightenment Elizabeth

The first source, also the oldest, is Observations and remarks upon the lives and reigns of King Henry VIII. King Edward VI. Queen Mary I. Queen Elizabeth, and King James I., written in 1712 at the latest by an unnamed author. This work is part of a larger history of England, potentially intended for the use of King Charles II. It was written just before, or at most during the very beginning of, the Enlightenment Era. This era was significant to historiography because of its emphasis towards progress and idealism, described in more detail here. However, Renaissance historians were more influenced by religion than their Enlightenment counterparts, but did subscribe to the idea that tangible human causes were at work in the story of history.

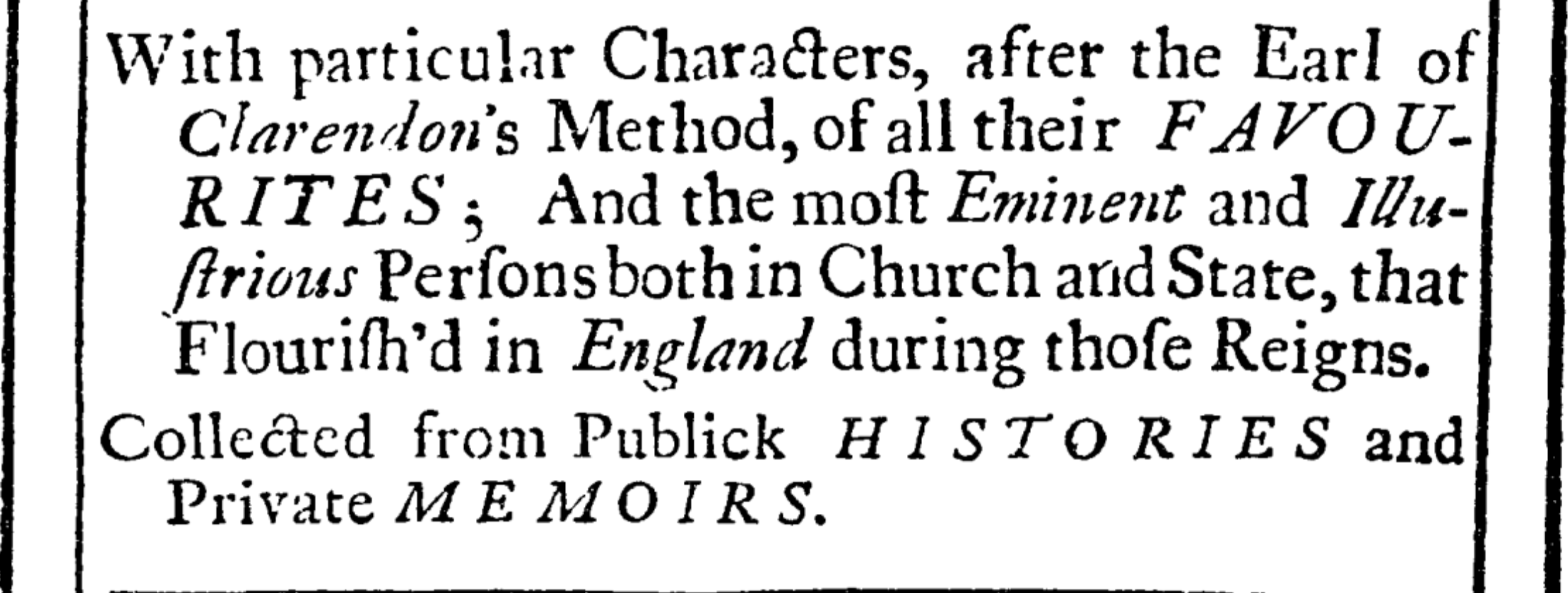

The structure of this work is certainly not recognizable to modern historians. Firstly, there are no sources cited, merely a mention of their existence at the beginning:

Elizabeth’s chapter begins with her heritage, her childhood, and her claim to the throne, all in short order. It then describes her conflict with her sister and predecessor, Queen Mary, culminating in her coronation at the age of 26. It is here that we can again see the difference with which historians approached their histories:

…Fortune finding, that her time of Servitude Expir’d at her Sister’s death, she put a Scepter in her Hand, and a Crown upon her Head, as a Reward of her Patience. This happen’d in the 26th year of her Age, a time in which with respect to her External Endowments she was full Blown, and for Internal Qualifications, she was grown Ripe, and Season’d with Adversity…

And on it goes in this style. There are two things here to note. The first is the heavily biased nature of the document: rather than say Elizabeth became Queen at her sister’s death, the historian chooses a heavily narrative style characteristic of these early histories.

The second object of interest is the particular attention paid to her external features, which continue at length in this chapter. The other monarchs in this book, all male, have only cursory descriptions of their appearances. This indicates a priority placed in the culture at the time on the physical maturity of a woman. This work continues to approach Elizabeth in a markedly different way than the other monarchs, spending more time on her appearance and personality than her governmental decisions or her contributions to the Reformation period. One point, however, remained nearly the same in her chapter as the others, which is that of her favorites.

“Favorites”, as they are often called in reference to Elizabeth and other monarchs, are typically romantic interests of the King or Queen, given priority in their opinions on matters of state and other governmental decisions. I’ve previously mentioned Robert Dudley of Leicester, a particular favorite of Queen Elizabeth. Here is what this author has to say about him:

“I cannot agree with the common received opinion that the Earl of Leicester was Absolute and Superior to all others in her Favour; for tho’ I am somewhat short in the Knowledge of the times, I am well assured, from very good Hands, that the contrary was apparent…” (218).

They go on to describe that Dudley must not have had any particular control over Elizabeth, indicating that she could not have, therefore, held him in her favor. This indicates how the author feels about the strength of a woman’s character, even that of a Regnant. It also shows the heavily narrative quality of historical accounts at the time. They read like fiction, not history, which one does not have to be well-trained in historical methodologies to see.

A Rankean Elizabeth, with a nod to the past

The second source, written in 1896, is simply titled Queen Elizabeth, by J.E. Neale. This era places it firmly after the introduction of Ranke’s philosophy of history, which emphasized objectivity, peer review, and a standardized methodology still recognizable to modern readers.

This is, in some ways, a Rankean approach to Elizabeth’s life, with chapters in chronological order addressing different aspects of her reign. However, we can see here that Rankean historiography did not have complete control. In this book, there are no references, and no bibliography. However, the author directly addresses this, saying the book is not meant for historical research purposes. This indicates the perspective of the time, which was only beginning to place high value on more modern historical methodology.

In terms of its approach to Robert Dudley, the book has a different perspective than the first source:

“It is not strange that a lively young woman of twenty-five, unmarried, and living, so to speak, as the hostess of an exclusive men’s club- the Court- should delight in the company of one of its most fascinating members. Nor is it strange that she felt an emotional response to his manhood” (77).

Here we can, again, see two phenomena at play: that of historical thinking and of the view of women historically. The former is a clearly biased statement, one of opinion which wouldn’t be allowed in a more conventional historical account. The latter is the undermining of a queen, based primarily on the fact that she is a woman. Rather than compare her to other regents in her family, known especially well for their sexual appetites, she is instead illustrated here as a frivolous young woman of the author’s imagining.

A Postmodern Elizabeth

The third source, The Progresses, Pageants, and Entertainments of Queen Elizabeth I, is much more recent than the previous two, and indicates sweeping changes in the field of history since the source before it. This book was written after the postmodern ‘revolution’, which turned away from traditional historicism, and focused its attentions more on microhistories.

This book takes that interest to heart. It does not tell an overall account of Elizabeth I’s reign, in whatever style was more popular at the moment. Instead, this work sits comfortably in the realm of microhistory, explaining an often-overlooked facet of the Queen’s life.

The book has several other elements more recognizable to the modern (or post-modern) reader. The first is simply that sources are consistently, rigorously listed in Chicago Style footnote format. Other things also stand out, like an extensive list of contributors made up mostly of women, three female editors, and substantial use of images make a book most conventional historians would consider ‘good’ history. Here is where we can see the typical balance found between the extreme ideas of the postmodern era and the rigidity of the Rankean: a book that follows every ‘rule’ of Rankean history, while investigating a highly postmodern subject.

But what does a book of this nature, written mostly by women and very little about the conventional Elizabeth, have to say about her most popular love interest? Almost the same thing as everyone else:

“The attentiveness and proximity to the Queen of Robert Dudley, partly from his duties as Master of the Horse, led to scandalmongering about the real purpose of Elizabeth’s frequent progresses. In Ipswich, a citizen claimed that Elizabeth ‘looked like one lately come out of childbed’; about her progress in 1564, ‘Some say that she is pregnant and is going away to lie in.’ Another rumor asserted that ‘Lord Robert hath had fyve children by the Quene, and she never goeth in progress but to be delivered.’ Such rumors present an unsurprising slander of a Queen who loved travel, men, and power” (42-43).

So much of this book avoids the more scandalous side of writing history, but to be fair, it’s hard to avoid such a juicy topic. However, this piece at least takes a less condescending approach: rather than comparing Elizabeth to a young, impressionable woman, these authors compare her to Kings.

So what does this all mean?

There aren’t a lot of opportunities to understand how historians thought of women, because they didn’t write about us very much. The silence, in its own way, speaks volumes, in a way well represented by post-modernist feminist thinkers of the 20th and 21st centuries. However, by looking at a queen, especially a queen well-loved by her people, too hard for men to ignore, we can start to understand an overal conceptualization of women in different eras. There are other ways of going about this, like looking at witches, fictional characters, and saints. That is our job, as modern historians: we have the responsibility to find the stories that were left out of history books, or barely included, and make sure those stories get told. The point of historiography, in this sense, is to think critically about the way we write these new stories, and understand not just what they say about the subject, but about us.

2094 words.